In the 19th century gender inequality in society was in full force with women regarded as subservient to men and dependent on male support. Women were known in their capacity as daughters, wives or sisters and obituaries of upper and middle class women often focused on the accomplishments of their male relatives. They were expected to marry and uphold the values of Victorian society, an ideal which placed the women in the home as caregivers sacrificing everything for their children and playing the perfect hostess and submissive wife.

The painting above from 1868 called The Four Seasons of Life: Middle Age – The Season of Strength, shows the dutiful wife with her well behaved children welcoming her husband home from work. [1]

The Angel in the House, a narrative poem by Coventry Patmore from 1854 came to represent the ideal of Victorian femininity and how ‘Man must be pleased; but him to please, is woman’s pleasure’. For this reason, some women chose not to marry. These spinsters were not desperate for husbands, as history has unkindly described them, but courageous and confident wanting to lead their own lives and make their own decisions.

In 1871 advocates for women’s education, Maria Grey (left) and her sister Emily Shirreff wrote:

‘A woman should be reminded… that in marrying she gives up many advantages. Her independence is, of course, renounced by the very act that makes her another’s. Her habits, pursuits, society, sometimes even friendships, must give way to his.’ (quoted by Sheila Jeffreys in The Spinster and her Enemies, (1985) p.88). [2]

With upper class women unable to pursue a career during the 19th century, they instead used their intelligence, knowledge and skills to pursue charitable activities, such as volunteering, leading campaigns and raising funds for noble causes. Women were often involved in philanthropy helping the sick, poor and needy – a precursor to today’s charity and social work.

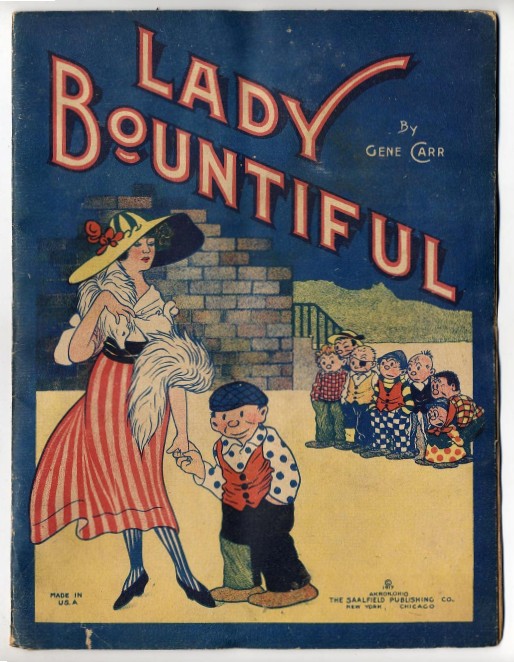

But whilst male philanthropists were celebrated with statues and had libraries and universities named after them, female philanthropists were unlikely to have such recognition. They were sometimes referred to as Lady Bountiful, a term with both positive and negative connotations. The name came from a character in a play from 1708 called The Beaux’ Strategem by George Farquhar, where a young scoundrel having blown his money in London plans to marry Lady Bountiful’s daughter for her large dowry.

Following the play, the term Lady Bountiful came into familiar use to describe an upper class woman who devoted her time and money to the betterment of those less fortunate. Seen in a positive light, the Lady Bountiful raised money to help the poor or gave out blankets to the homeless, a good deed and an act of kindness. The term was used both in the UK and US.

This image from Gene Carr’s comic strip ‘Lady Bountiful’ appeared in US newspaper magnate William Randolf Hearst’s Sunday newspapers from 1903. In the comic strip, Lady Bountiful was a gentle, softly-spoken, independently minded women of means who befriended street urchins in an attempt to lift them out of poverty. [3]

But society also deemed their charity as self indulgence only undertaken to impress others. This could also be true of men, but there was no such negative term used to describe them. The Cambridge University Press dictionary defines Lady Bountiful as, ‘a woman who enjoys showing people how right and kind she is by giving things to poor people’ (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Who were these female philanthropists, these Lady Bountifuls, what did they do and how were they regarded by society?

I am currently researching a number of women to bring their lives and work to light. If you can help add to their stories, please get in touch at spinstorian@gmail.com.

Alice Forbes (1852-1929)

Alice was born in Clifton, Gloucestershire to Alicia Wauchope and James David Forbes from Edinburgh. The family spent their summers in Pitlochry, Perthshire, Scotland and Alice kept her connections with the area, as a tenant from the 1890s to 1910. At its inauguration in 1895, she acted as Honorary Superintendent of the Pitlochry Nursing Association. Alice moved to Golders Green in London around 1910 where she lived until she died on 5 February 1929. Her obituary in the Hendon and Finchley Times (15 February 1929) portrays her entirely in relation to her male support. It is headlined ‘A Baronet’s Granddaughter’ and reads, ‘The late Miss Forbes came of a distinguished family. She was daughter of the late Principal, James David Forbes, St Andrew’s University and her grandfather was Sir William Forbes, Bart. of Pitsligo.’ There is no mention of Alice’s life or her endeavours.

Marion Jane Stirling Stuart (1861-1953)

Marion was youngest daughter of the Stirling Stuart family of Castlemilk House in Carmunnock, Lanarkshire, Scotland. Her mother was Harriet Boswell Erskine Fortescue and her father, James Crawfurd Stirling Stuart. Marion, like Alice Forbes, whom she knew, holidayed with her family in Pitlochry, also living there on and off between 1891 to 1900. From 1897 she acted as Honorary Secretary to the Pitlochry Nursing Association, moving to Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire in 1900 to set up a convalescence home, St Margaret’s (previously known as Tickford Lodge) with Sister Louisa Mary. She died on 24 March 1953 and is buried in the Stirling Stuart vault in Carmunnock Parish Churchyard.

Image Credits

[1] The Four Seasons of Life: Middle Age — The Season of Strength, Currier and Ives, 1868 (Wikimedia Commons).

[2] Photograph of Maria Grey, 1880 (Wikimedia Commons).

[3] ‘Lady Bountiful’ cartoon by U.S. cartoonist Gene Carr, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons).

Copyright (c) Ruth Washbrook 2023 / third party copyright holders